Hypertext Monuments

Posted by <Rachel Jackson> on 2022-10-15

Hypertext Monuments, laser-engraved plastic, found imagery, inkjet on vinyl, MDF, 12 x 12”

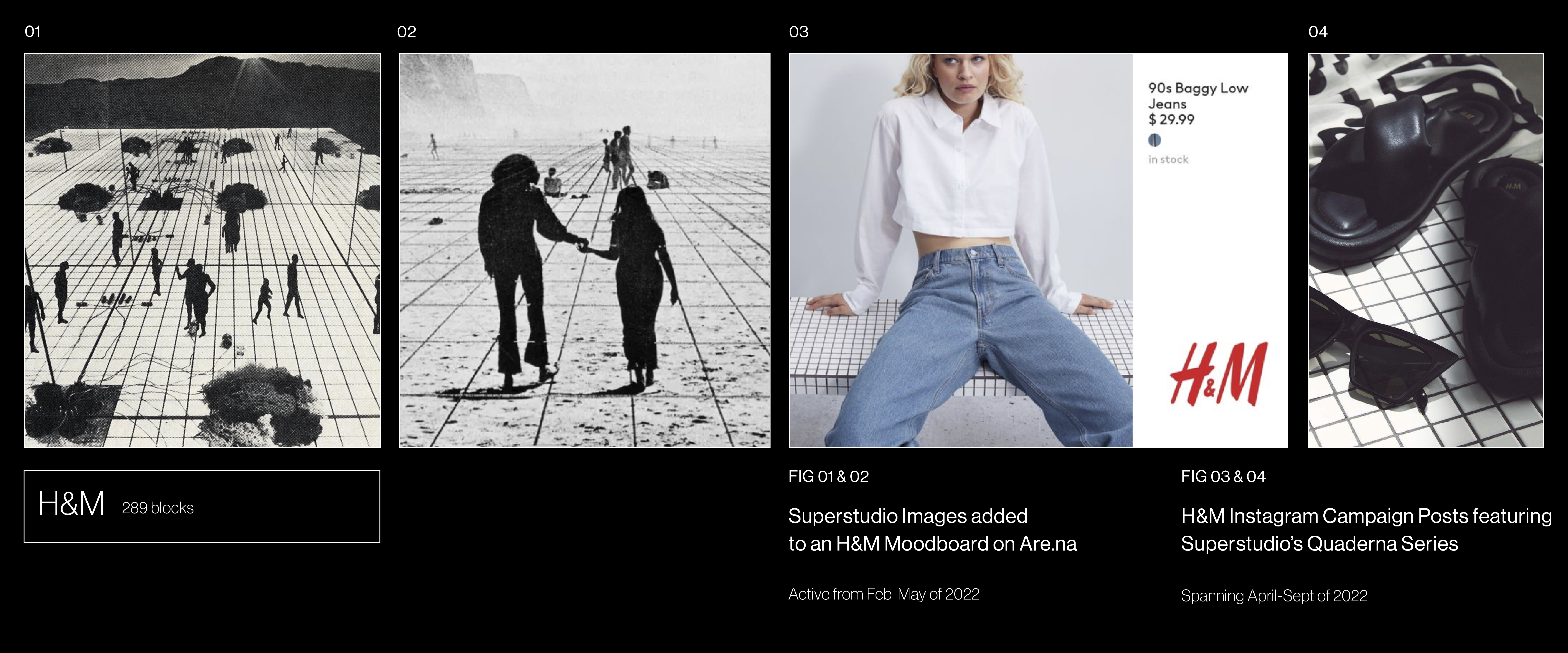

I’ve spent the past few months tracking the circulation of a set of images: grainy, low resolution scans documenting the work of the Italian Radical Design group, Superstudio. These images seem to find their way into every niche of moodboarding, particularly on the visual research platform, are.na. They can be found on boards for an H&M seasonal campaign, album cover inspiration, research for an architecture thesis...Like most content relegated to image aggregation sites, reference to their origin is often erased and they are rechristened with titles derived from metadata. What were once imaginings of a “life without objects,” become eye candy ripe for commercial appropriation. Stripped of meaning, these images are transplanted into channels where they exist in the company of vastly dissimilar imagery, ranging from robot_examines_body_in_bagdad.jpg to BritneySpears_portrait.jpg.

As a means of examining this strange compression of time and context, I began collecting any images that neighbored the original Superstudio images. Ultimately, I pasted them back onto forms similar to ones that I encountered throughout my research, pieces that, after processing through a reverse image lookup site, I discovered were sculptures created by a Florentine interior designer, Duccio Maria Gambi. Since these forms were based on Superstudio’s Quaderna series, It felt fitting to fuse them with the disseminated images I had gathered. Tracking the dispersion of these images through various channels of art direction allowed me to witness their commercial appropriation in real time and examine the contemporary role of the image aggregator.

On Superstudio

I chose to treat Superstudio as a control group within my casual research, mainly because my familiarity with them stemmed from several years of encountering their work online with no understanding of their ideology. I imagine it’s like this for many others who encounter their work outside an academic setting–it’s visually compelling and inoffensive enough that it appeals to an extremely broad scope of audiences. It’s the rare kind of content that snagged reblogs from teenage girls on tumblr in 2014 while simultaneously garnering attention from Domus and Artforum.

Operating out of Florence from 1966 to 1978, Superstudio’s ideology was largely informed by the Operaismo movement prevalent throughout Italian left-wing politics of the 1960s-1970s. Steeped in Marxism and allied with student activism of the era, Operaismo focused on the potential of the working class as a source of rupture that could be weaponized against a capitalist system. Through speculative architecture, often photomontages featuring their signature grid, Superstudio created jointly utopian/dystopian visions that depicted individuals liberated from consumerist desire, inhabiting superstructures seamlessly embedded in natural landscapes. The grid, used as the building block for Superstudio’s imagined buildings, was intended to function as a democratizing force, freeing inhabitants from social stratification by allotting equal property to all. Despite its outward idealism, Superstudio’s Continuous Monument series was a project dually tinged with irony, satirizing rapidly occurring globalization through monumental, impossible structures. At its core, Superstudio’s ideology emphasized hyperconnectivity, pioneering the concept of a networked society years prior to the birth of the internet.

While the majority of Superstudio’s practice revolved around fictional intersections of ecology and urbanism, their gridded “wireframes” were also applied to a system of furniture designs. Occurring in several different iterations, including a writing desk and a dining table, Superstudio’s Quaderna series consisted of wood furniture encased in 3x3 cm gridded laminate, This pattern, also referred to as “Misura,” was applied to domestic objects in an attempt to distill them into their most minimal forms. Through this, the Quaderna series sought to relieve class-related status anxiety by creating a truly “neutral surface.”

Despite the primarily conjectural nature of Superstudio’s practice, their impact on the field of architecture and design remains prominent. The recent unveiling of plans for “The Line,” a 75-mile linear city to be constructed within the desert of Saudi Arabia, bore a striking resemblance to Superstudio’s Continuous Monuments. It spurred a response from one of Superstudio’s last living members, Gian Piero Frassinelli, who lamented, “Seeing the dystopias of your own imagination being created is not the best thing you could wish for.”

The Image Aggregator

Sourcing imagery for Hypertext Monuments led me to question the politics of image distribution. In an era when Web 2.0 platforms minimally benefit artists yet remain one of the chief methods of exposure, what does it mean when radical intentions are expunged in favor of surface level aesthetics? How do we reckon with this as artists when social media platforms have integrated image aggregation into their in-app features (i.e. the ability to save any image to a user’s personal boards on Instagram, browser plug-ins that streamline compiling links). These tools make it easier than ever to amass a library of visual references. The online landscape of image aggregation, originally birthed by “surf clubs,” then succeeded by tumblr, has been largely usurped by creative agencies that recognize the marketability of mimetic imagery. The primary demographic of image collectors has pivoted from those who curated pseudo-spiritual personal aesthetics to those interested in monetizable brand creation.

R Gerald Nelson, in his novel DDDDoomed, Or, Collectors & Curators of the Image, delineates two kinds of image aggregators–those who “present disparate images as a way of portraying the idiosyncrasies of our culture, against those who narcissistically and merely attempt to communicate one’s keen eye for style and trends.” The corporate image aggregator, in their effort to curate topical brand identities and campaigns, becomes a catalyst for image deradicalization and inherently falls into the latter category. In my browsings I encountered: a black panther icon pinned next to the Bayer wordmark as “logo inspiration,” a gif of a self-immolating Buddhist monk on a moodboard entitled “DRUNK IN LOVE”, and an image of an armed security guard posing next to the Davos sign at the World Economic Forum of 2021, amongst many other jarring inclusions. This genre of charged imagery does not seem to be pulled critically as Nelson’s first category suggests– instead it appears to be an unintended consequence of cursory visual consumption that prioritizes aesthetic merit over context.

In this realm of engagement, the aggregator is often concerned with sourcing images that convey a trend-adherent look, sometimes based on a set of given brand attributes. The black panther icon is viewed as worthy of visual imitation and perhaps valued for its formal qualities. A gunman posing on the Davos sign possesses an edginess that elicits enough intrigue to make its way onto a “riot porn” moodboard. I’ve witnessed the same mindset applied to the work of living artists–recently I saw stills from Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue pulled as inspiration for a fashion campaign, and another brand’s moodboard featuring Trevor Paglen’s drone photographs, likely romanticized for their pastel, gradient compositions.

Perhaps there is some way to distort this pattern, to institute images into circulation as The Jogging did and coyly manipulate trend cycles. I’ve been placing the Hypertext Monuments back into the are.na boards where their imagery was originally sourced, as a means of returning them back into their initial habitats. If cycles of image transmission are inevitable, maybe the best way to counter them is to play into decontextualization and imitation. There is an influencing power present in the moodboard, particularly on are.na where open collaborative channels allow imagery to be planted by other users. I see them as one means by which hyperstitions can be realized and visual landscapes can be manipulated.